Citrus Canker

History:

Citrus canker was first detected in Florida in 1910, affecting trifoliate rootstock seedlings that had been imported from Japan. The disease quickly spread across the Gulf Coast, from Texas to Florida and up to South Carolina, likely due to the transportation of contaminated plant material. In 1915, a quarantine was implemented and an extensive eradication effort was initiated, which successfully eliminated the disease by 1933.

However, a second outbreak occurred in 1986, when citrus canker was discovered in residential citrus trees in the Tampa Bay area of west-central Florida. The disease subsequently spread to nearby commercial citrus groves. Despite concerted efforts to control the outbreak, citrus canker was not fully eradicated until 1994.

In September 1995, a new outbreak of citrus canker was detected in residential citrus trees close to the Miami International Airport in Miami-Dade County. Despite a third eradication attempt, the disease continued to spread due to the impact of hurricanes in 2004-2005, eventually affecting 25 counties in the region. The initial effort to eradicate the disease involved the destruction of 2.1 million commercial and dooryard trees by 2003. However, the program was discontinued in January 2006, as the disease had become so widespread that eradication efforts were no longer practical.

Consequently, the citrus industry has had to adapt to living with and managing the impact of citrus canker while maintaining high-quality fruit production.

Citrus Canker

Causal Organism:

Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri and Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. aurantifolii are two types of bacteria that cause citrus canker, a disease that affects citrus trees. Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri is known to cause citrus canker in a range of citrus fruits, while Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. aurantifolii primarily affects lime and lemon trees.

Hosts:

There are many different species, cultivars, and hybrids of citrus and related plants, which include orange, grapefruit, pummelo, mandarin, lemon, lime, tangerine, tangelo, sour orange, rough lemon, calamondin, trifoliate orange, and kumquat.

Symptoms:

- Citrus canker primarily affects the leaves and fruit rinds of citrus plants, causing blemishes and spots.

- However, under favorable conditions, the disease can also lead to defoliation, shoot dieback, and fruit drop.

- Symptoms of citrus canker include the appearance of brown spots on leaves that may look oily or water-soaked.

- These spots, known as lesions, are usually surrounded by a yellow halo and can appear on both sides of the leaf. Similar symptoms may also be present in fruit and stems.

- In addition, damage caused by the Citrus Leafminer (CLM) can increase the risk of citrus canker infection.

- The CLM larvae create shallow tunnels or "mines" on leaves, exposing more tissue to the disease and increasing the areas that become infected.

- In fact, the photo provided shows a leafminer tunnel with visible citrus canker symptoms.

Disease Cycle:

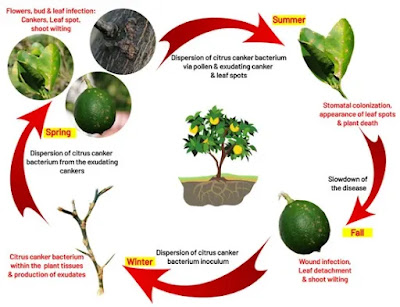

Bacteria multiply within the lesions that develop on leaves, stems, and fruit. When moisture is present on the lesions, the bacteria can ooze out and spread to infect new growth. Wind-driven rain is the primary means of dispersal, and wind speeds of 8 m/s (18 mph) or greater can aid in the penetration of bacteria through stomatal pores or wounds caused by thorns, insects like leafminer, and blowing sand. Pruning can also cause severe wounding and lead to infection.

Bacterial multiplication mainly occurs while the lesions are still expanding, and the number of bacteria produced per lesion is related to the general susceptibility of the host. A drawing of the disease cycle can illustrate this process.

The bacteria can remain viable in the edges of the lesions present in leaves and fruit until they separate and fall off. Bacteria have been found to survive in lesions on woody branches for several years. Bacteria that exude onto plant surfaces are not viable and begin to perish when exposed to rapid drying. Direct sunlight also accelerates bacterial mortality.

Survival of exposed bacteria is limited to a few days in soil and several months in plant residue that is mixed into the soil. In contrast, bacteria can survive for years in infected plant tissue that has been kept dry and free of soil.

Spread and Movement:

When wet, the lesions caused by citrus canker release bacterial ooze that can infect new growth and be carried over short distances by wind, rain splash, and overhead irrigation. Floods and cyclones can also lead to the long-distance spread of the disease, as can human activities like the movement of clothing, equipment, and infected plant material (such as rootstock seedlings, and budded trees).

Plants become infected when bacteria or bacterial spores enter through natural openings or wounds on leaves, growing shoots, and fruit. The disease can also be spread by birds, insects, and humans, especially when trees are wet.

The bacteria can survive in diseased plant tissue and in soil and can overwinter in angular shoots, becoming active again in the following season.

Control

Exclusion:

The initial strategy in preventing citrus canker is to exclude the pathogen. Some countries or regions have successfully prevented the establishment of X. axonopodis pv. citri due to strict regulations on the importation of propagating material and fruit from canker-infected areas. However, the increased global movement of people and goods raises the risk of pathogen introduction. In Florida, for instance, there have been six documented cases of citrus canker reintroduction since 1985, highlighting the ongoing challenge of pathogen management and control.

Sanitation:

Human and mechanical transmission are common ways in which citrus canker is spread. Bacteria can be carried on various objects, such as clothing, gloves, hand tools, picking sacks, and ladders, and even on the skin. Vehicles, machinery, and equipment can also become contaminated and spread the disease. To prevent the spread of citrus canker, it is essential to establish decontamination stations where personnel, vehicles, and machinery can be treated with bactericidal compounds. This is particularly important in areas where citrus canker is present.

Eradication:

The most commonly accepted method for eradicating citrus canker is to remove and destroy infected and exposed trees. This can be done by uprooting and burning trees, or by cutting them down and chipping them in urban areas, with the refuse being disposed of in a landfill. In Florida, state law mandates the removal of all citrus trees within 579 m (1900 ft) of infected trees in both residential and commercial settings.

Economic Impacts:

- Florida has experienced two large-scale eradication efforts for citrus canker, one between 1915 and 1933 and another in the 1980s.

- The more recent eradication effort involved burning over 20 million trees at a cost of almost $94 million.

- The economic impact of citrus canker is significant, including potential losses in citrus quality and productivity, regulatory restrictions on fruit shipment, and costly eradication efforts.

No comments:

Post a Comment